Death of the King of the Herd; Indian Pursuing Buffalo; Indian and Buffalo Group; The Chase

Banner Image: Alexander Phimister Proctor

Buffalo Hunt, 1917

Bronze, 18 1/4 in. (height). Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Gift of A. Phimister Proctor Museum with special thanks to Sandy and Sally Church. 4.08.3

Plate 10.1 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

Jackson Sundown, ca. 1915

Photography, b&w. Alexander Phimister Proctor Collection, MS 242, Harold McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. P.242.761

For Proctor’s singular portrayal of a buffalo hunt, he selected a set of heroic characters that would perform the chase in as dramatic a way as possible. The artist had neither seen nor participated in such a pursuit, so the piece was informed totally by his larger-than-life view of what hunting was all about—a grand and mortal contest between man and nature. To magnify the human element in the scene, he selected none other than one of the survivors of the Nez Perce War, Chief Joseph’s nephew Jackson Sundown. Also, as a means of building credibility for his personal creative endeavor, Proctor moved himself and his family for a summer into a teepee owned by Sundown on the Fort Lapwal Reservation near Lewiston, Idaho. And to reflect his own identity as an intrepid hunter of trophy animals, he selected an epic-sized buffalo bull as the quarry. These ideal elements were all connected at close quarters by a spear that, thrust by one of the actors in the drama, was intended to complete the sculptural narrative. It was an allegory to native vibrancy, nature’s revolving saga of life and death, and the incredible energy that Proctor saw embodied in the West.

Plate 10.2 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

Running Buffalo, (study for Buffalo Hunt), 1916

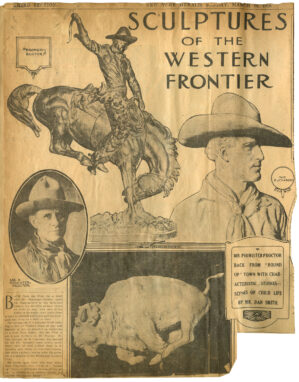

Plaster. Illustration in New York Herald (March 12, 1916, 3rd sec.). Alexander Phimister Proctor Collection, MS 242, Harold McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. MS242.OS10.01.16

The pieces of this sculptural amalgam are more complex than they might appear. The bronze does celebrate the Plain Indians’ dependence on the buffalo for survival and Native people’s powerful link with their primary means of sustenance. The model the artist chose, Jackson Sundown, [Plate 10.1] however, was famed not as a hunter, but rather as one of the most celebrated champion rodeo bronc riders of his day. In a reversal of roles, Proctor elected to live near Sundown in a teepee because that was the only way his model would agree to pose for him. The teepee served as Sundown’s guesthouse, and the price was right, the location convenient, and the structure large enough for a full gaggle of Proctors. A magnificent mature buffalo bull would probably have been the last animal in a herd that Plains Indian hunters would have selected. They preferred cows or young bulls and heifers for their relatively tender meat.

Proctor began his buffalo hunt sculpture by portraying a running buffalo, which he completed by the spring of 1916 and illustrated in the New York Herald.[1] [Plate 10.2] As a singular work of art, the plaster was superb. The beast’s legs were tucked under him as he thundered across the presumed prairie floor.

Plate 10.3 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

Buffalo Hunt, ca. 1916

Plaster, 7 7/8 in. (height). Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Gift of A. Phimister Proctor Museum with special thanks to Sandy and Sally Church. 11.06.486

It is thought that Proctor next conceptualized the full hunt scene as a plaster relief. [Plate 10.3] It is a remarkably spirited work. When the buffalo was combined with the Indian rider in the three-dimensional sculpture, though, the scene was freighted with noticeable disparities. [Plate 10.4] One critic pointed to the extraordinary “energy, activity and unusual alertness” of the Indian, while the buffalo was knotted up with “fear and anger.” The “huge bulk of the bison” was also contrasted with the “slender grace of the horse.”[2] There appeared to be a hierarchy of players, the vigilant hunter subverting the lumbering prey. The work suggested to the same critic an opportunity not just for grading within the narrative structure of the piece but for an assessment of creative forces as well. Proctor was said in this work to have “a fine feeling for artistic values”—contrary, he extolled, to what he regarded as the “erratic” shortcomings of Frederic Remington’s sculptural work.[3]

Plate 10.4 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

Buffalo Hunt, 1917

Bronze, 18 1/4 in. (height). Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Gift of A. Phimister Proctor Museum with special thanks to Sandy and Sally Church. 4.08.3

The dramatic ensemble, titled The Buffalo Hunt, was cast in 1917 and copyrighted the same year. Most viewers took it for what it was, a remembrance of times gone by, and regarded it as an example of the age-old myth of the vanishing Indian. As one reporter wrote in 1917, “Mr. Proctor has come to be recognized as indeed an historian, his sculptured works of fast disappearing western types being a link between what is soon to be the past, and the future.”[4] Ironically, although the author suggested in the title of his article that Proctor was to make Sundown, the grand winner of that year’s Pendleton Round-Up, “immortal,” it was not as a bronc rider that the eternal recognition befell him, but as a staged “type” from a bygone era. Nonetheless, Sundown was proud to play the role and even posed in a feather bonnet for a companion bust portrait that Proctor titled Sundown, Nez Perce Chief. [Plate 10.5]

Plate 10.5 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

Sundown, Nez Perce Chief, 1917

Bronze, 11 1/2 in. (height). Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Gift of A. Phimister Proctor Museum with special thanks to Sandy and Sally Church. 18.08.5

A three-dimensional plaster of The Buffalo Hunt was exhibited in the spring of 1917 at the Art Institute of Chicago as The Chase and illustrated in the museum’s Bulletin.[5] Most of the known subsequent bronze versions of The Buffalo Hunt were produced as sand casts by Gorham Co. Founders. One of the earliest such castings was acquired by the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1918 and is now in the collections of the National Gallery of Art. It was purchased directly from an exhibition at the Corcoran, Works in Sculpture by Alexander Phimister Proctor, which ran through most of March of that year.[6] Considering that the United States was deeply immersed in World War I at the time, this was a fortunate and timely sale.

The Christian Science Monitor, which reviewed Proctor’s Art Institute showing, claimed that he seemed to be “continually hampered because the medium of sculpture will not allow his animals to run in mid-air.”[7] Yet not only the buffalo but also the horse and rider are suspended above the ground by the introduction of a large, sweeping bunch of sagebrush. Proctor had, indeed, achieved his goal of supplying verisimilitude in action.

[1] Dan Smith, “Sculptures of the Western Frontier,” New York Herald (March 12, 1916). See also Ebner, Sculptor in Buckskin, 168.

[2] Frank Owen Payne, “Two New Bronzes by A. Phimister Proctor,” unidentified clipping, c. 1917, Proctor Archives.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Proctor’s Sculpture Will Make Immortal Winner at Round-Up,” Portland Oregon Journal (February 11, 1917).

[5] Small Bronzes by A. Phimister Proctor (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1917), no. 33, and Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 11 (April 1917), 308.

[6] Works in Sculpture by A. Phimister Proctor (Washington, D.C.: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1918), no. 13.

[7] “Chicago Institute of Art Has Seven One-Man Shows,” Christian Science Monitor (April 6, 1917).