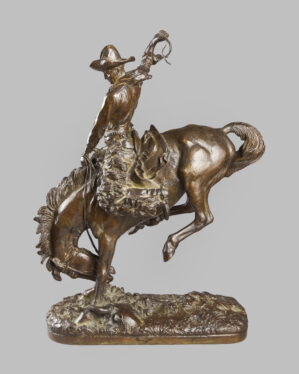

Banner Image: Alexander Phimister Proctor

Buckaroo, ca. 1915

Bronze, 26 1/4 in. (height). Denver Art Museum Collection: Funds from William Sr. and Dorothy Harmsen Collection by exchange, 2005.12. Photography: Denver Art Museum

Plate 8.1 — Joseph Jacinto Mora (b. Uruguary, 1876 – 1947)

Fanning a Twister, 1913

Bronze. Illustration in Scribner’s Magazine 55, (January – June, 1914), 665. Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming

In the winter of 1913–14, the National Academy of Design hosted its annual winter exhibition, which included 119 representative works by American sculptors. Proctor exhibited one bronze, a small cast of Buffalo for the Q Street Bridge in Washington, D.C.[1] For this he received the praise of art critic William Walton in Scribner’s Magazine for having contributed one of the truly “modern additions to the repertory of art.”[2] The Buffalo was perhaps the artist’s prime achievement as a sculptor of animals. Its powerful simplicity was indeed a modern statement, and the vibrant majesty and monumental proportions of even this small version proved how far Proctor had come since his first sentimental efforts with his two versions of the Fawn (see plate 1.2) twenty years earlier.

Plate 8.2 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

Buckaroo, ca. 1914 – 1915

Plaster, 28 in. (height). Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Gift of A. Phimister Proctor Museum with special thanks to Sandy and Sally Church. 11.06.698

Yet when Proctor visited the National Academy show and later read the Walton review, he must have been drawn to an especially vital western bronze by California artist and fellow academician Joseph Mora. Titled Fanning a Twister, [Plate 8.1] the work embodied something his Buffalo lacked in profound measure. Mora’s work was all action and spirit, all energy and dynamism. Unlike Proctor’s Buffalo with its static grandeur, Mora’s little bronze brimmed with ebullience. Proctor must have wondered what it would be like to return to the West, as he had so often done over the years, but this time with the intent not of hunting wild animals, but of bringing the contemporary human elements of the western scene to life through his art. The cowboy—having been celebrated in sculpture since 1893 with Proctor’s plaster monument Cowboy at the World’s Columbian Exposition, and in 1895 with Frederic Remington’s masterpiece The Broncho Buster—was the perfect theme. Proctor had no doubt seen the latter work in the New York showroom windows at Tiffany’s and probably even knew of Charles M. Russell’s explosive 1911 sculpture of the same subject, A Bronc Twister, which was displayed in the shop of Theodore Starr on Fifth Avenue. But neither of these sculptors was currently showing at the National Academy. Mora was likely the most logical inspiration for Proctor. Now, Proctor surely concluded, the subject as well as Mora’s pose needed his touch. Somehow he would have to find a way to lend his hand afresh to the cowboy’s interpretation.

By the next time he saw another of Mora’s bronco sculptures, one called Scratching a Twister in the Fine Arts Pavilion of the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, Proctor had fulfilled his wish and produced his own bucking horse and rider.[3] During a visit to Oregon’s Pendleton Roundup the previous summer, Proctor had embarked on a bucking-horse sculpture with his own mix of powerful aesthetic design and stylistic restraint. It was elegant, graceful, and controlled, yet at the same time spirited. He had suffered some false starts that fall and even a studio fire that destroyed the first of his cowboy models, but with perseverance, he was back in the Northwest the following summer with what local newspapers referred to as six bronze castings (though they were probably plasters) of western subjects, including one that he had copyrighted under the title Buckaroo.[4] The first showing appeared in Seattle at the Washington State Art Association galleries.[5] Proctor then displayed the works in the private residence of Mr. and Mrs. John G. Edwards of Portland, where his cowboy sculpture was singled out as an exceptional tour de force and the representation of a national icon. The sculpture was “full of verve and action, both horse and man typically American, typically Western,” wrote the Morning Oregonian. Yet even as the sculptor demonstrated a primary interest in the “expression of action,” the reporter continued, “he never loses the rare sense of decorative beauty which is characteristic of his more monumental works.”[6] When a plaster cast of the piece [Plate 8.2]was sent to Pendleton in late July 1915, a local newspaper boasted that it would soon be converted into a monument for that city.[7] Unfortunately, that honor was not to be, but according to one of the local papers, the plaster model that had “created a furore [sic] in art circles” in Seattle and Portland had been well enough received to encourage the artist to send the plaster east to be cast in bronze.[8]

Plate 8.3 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

Buckaroo, ca. 1915

Bronze. Private Collection

Plate 8.4 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

Buckaroo (Gorham, detail – foundry mark), ca. 1915

Bronze, Private Collection

It is thought that the plaster was shipped in August to the Gorham Co. Founders in Providence, Rhode Island. There, according to the company’s records, a singular sand-cast bronze was completed by mid-September.[9] What is thought to be this initial bronze, or one much like it, is marked with a set of letters, QACQ, and the boxed-in symbol “G/[she wolf]/C,” [Plate 8.3 and Plate 8.4] which denotes an early cast. It was sent back to Oregon in early November, where, with great fanfare, the first Buckaroo bronze was exhibited in Pendleton.[10] The statue did not rest on its pedestal for long, however. Such was the enthusiasm for this bronze masterpiece that locals and supporters from across the state pressured Proctor to forward it immediately to San Francisco to adorn the galleries of the Oregon Pavilion of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Contending in a headline that it “Typifies Possibilities of Western Art,” the Portland Oregonian reported that the Buckaroo bronze had on November 12 been “unveiled in the art room” of the Oregon Pavilion. It proved, for Proctor at least, that the West held fresh possibilities for his art. He was present to watch the bronze emerge from beneath the drape of an American flag, and he then offered complimentary remarks about how Oregon had served him as muse. It was, he said, “an artist’s country. It is the natural haunt of creators.”[11] With this comment, Proctor positioned himself as a true creative son of the West. No subject could have done this more effectively than a bronze rider of wild horse flesh.

The records of the Gorham Co. Founders suggest that the plaster for Buckaroo was returned from Providence to New York City, either to the Gorham showroom there or to Proctor’s East 51st Street studio. In the meantime, using his clay model, Proctor evidently responded to what he foresaw as a stirring demand and produced a second plaster to be used by the Roman Bronze Works in Queens, New York. The resulting new castings were slightly different from the Gorham piece. In the Roman Bronze Works castings, the rider’s left hand is generally free from the horse’s mane, there is a hole visible in the mane, and the tail does not connect with the animal’s rump (see plates 8.6 and 8.8). The Roman Bronze Works ledgers record that in 1916 and 1917, no fewer than seven castings were made.[12]

Plate 8.5 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

Buckaroo, ca. 1916

Bronze, 27 1/2 in. (height). Oregon Historical Society, Portland, Oregon

One of those early Roman Bronze Works castings—all produced using the lost-wax, rather than the sand-cast, method—was ordered as a special presentation piece from the artist to his old Portland friend and promoter John G. Edwards (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut). Edwards had been a legendary cattleman and sheep rancher in Wyoming and eastern Oregon and, in his later years, was himself devoted to painting and sculpting. The Proctor bronze reflected Edwards’s love of art and his self-image as an adventuresome man of the West.[13] Another early lost-wax casting was made for a group of citizens from Pendleton who considered the Buckaroo [Plate 8.5] the quintessential symbol of their city and the West. For that reason they chose to make a gift of it to one of the city’s heroes, Charles Samuel Jackson, a pioneer newspaper man from Pendleton who had served as publisher of the Eastern Oregonian for twenty years before moving to Portland in 1902 to found the Oregon Journal. The presentation was made in January 1917. In gratitude, Jackson wrote that the city representatives “could not have selected a finer implement with which to emblazon upon my heart the good will of Pendleton.”[14]

Plate 8.6 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

George D. Pratt, 1935

Bronze, 7 1/4 in. (height). Amherst Library, New York, New York. Gift of the estate of Herbert L. Pratt / Bridgeman Images

It is not known which foundry’s casting Proctor took with him to Denver in 1917 when he attended William F. Cody’s funeral and, through the artist’s wife, fortuitously connected with the city’s mayor, Robert Walker Speer.[15] What is known is that Speer commissioned Proctor to turn the Buckaroo into a heroic-sized bronze monument for Denver’s new Civic Center and that the artist chose to enlarge the Gorham model and use Gorham Co. Founders for casting the monument. It was titled Broncho Buster and dedicated in 1920. To illustrate how open Proctor was with regard to his selection of foundries and how he liked to spread the work around, yet still obtain the most affordable castings possible, the production for the companion Denver monument, On the War Trail, was assigned to the Roman Bronze Works foundry in Queens. It was dedicated in 1922.

The Buckaroo was a favorite piece for one of Proctor’s major patrons, a frequent hunting companion from the early 1910s and Standard Oil Company’s president, George DuPont Pratt. [Plate 8.6] Between 1916 and 1932 Pratt commissioned at least three bronze castings of the Buckaroo from Proctor, two of them from Roman Bronze Works and one or more from Gorham. An early Roman Bronze Works casting, now in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, is specially marked, on the base, “CAST FOR GEO. D. PRATT / BY A.P.P.” [Plate 8.7] One other Roman Bronze Works bronze of the Buckaroo, ordered by Pratt for the Boy Scouts of America, is in the collections of the R. W. Norton Art Gallery in Shreveport, Louisiana.

Plate 8.7 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

Buckaroo, ca. 1917

Bronze, 28 1/2 in. (height). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York. Bequest of George D. Pratt. 48.149.26. Art Resource, NY

Pratt ordered more of these castings from Proctor to be manufactured by Gorham, as indicated by a surviving plaster model marked on one side of the base, “CAST FOR GEO. D. PRATT / A.P.P.” (Buffalo Bill Center of the West; see plate 8.3). Pratt also purchased at least one other casting from the Gorham Co. Founders, which he donated in 1932 to his alma mater, Amherst College, and is now in the collection of the Mead Art Museum. [Plate 8.8] It was cast in lost wax under subcontract by Eugene Gargani & Sons.[16] The arrangement with Gorham lasted until 1934, and at least one other casting, now located at the Denver Art Museum, is thought to have been the result of that agreement. [Plate 8.9]

Plate 8.8. — Alexander Phimister Proctor.

Buckaroo, 1932

Bronze, 26 1/2 in. (height). Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, Amherst, Massachusetts. Gift of George D. Pratt / Bridgeman Images

In 1935 Proctor placed an order for another Buckaroo from Roman Bronze Works for a Christmas present to the art collector and philanthropist Ernest E. Quantrell of Bronxville, New York, from his family (Rees-Jones Collection, Dallas, Texas). The casting of this latter bronze cost Proctor $210. In this case and that of Pratt’s Gorham casting, the “sale price” was listed as $475, though Pratt’s casting was discounted to $332.50 while the Quantrells’ bronze cost his family $400.[17] Pratt was a sufficiently loyal patron to garner a somewhat deeper discount.

Plate 8.9 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

Buckaroo, (Gorham / Gargani, detail – foundry mark), ca. 1915

Bronze. Denver Art Museum Collection: Funds from William Sr. and Dorothy Harmsen Collection by exchange, 2005.12. Photography (c) Denver Art Museum

A second, undated plaster model for this bronze exists [Plate 8.10] that is thought to have come from the Roman Bronze Foundry. In it, the horse’s rump is an inch or more higher than in earlier castings, and the reins are connected to the bridle near the throat of the horse rather than at the mouth. No lifetime bronze castings from this plaster are known to exist today.

Plate 8.10 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

Buckaroo, ca. 1918 – 1920

Bronze, 28 in. (height). Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Gift of A. Phimister Proctor Museum with special thanks to Sandy and Sally Church. 11.06.697

[1] National Academy of Design: Winter Exhibition (New York: National Academy of Design, 1913), 16.

[2] William Walton, “The Field of Art,” Scribner’s Magazine 55 (May 1914), 666.

[3] The Official Catalogue of the Department of Fine Arts, Panama-Pacific International Exposition (1915) lists and illustrates Mora’s bronze.

[4] For reference to the studio fire, see “Sculpture on Exhibit,” East Oregonian (November 16, 1914). The copyright was filed from New York on July 8, 1815. Images of the works that were illustrated in the newspapers at the time appear to be depictions of plasters, not bronzes. See, for example, “Sculptor Is Guest,” Portland Morning Oregonian (July 23, 1915).

[5] “Noted Sculptor Exhibiting in Seattle,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer (July 21, 1915).

[6] “Sculptor Is Guest.”

[7] “Famous Statue to Be Exhibited Today,” Pendleton East Oregonian (July 29, 1915). The sculpture, referred to clearly as a plaster cast, was shown at the Frazier Book Store in Pendleton. The city’s other newspaper referred to the work as a plaster also. “To Exhibit ‘Buckaroo,’” Pendleton Tribune (July 29, 1915).

[8] “To Exhibit ‘Buckaroo.’”

[9] Samuel Hough, “Report on Gorham Foundry Casting QACQ: A. Phimister Proctor’s ‘Buckaroo,’” undated record for Buckaroo, no. 8.2.1, Proctor Archives, McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West (hereafter cited as Proctor Archives).

[10] “‘Buckaroo’ on Exposition,” East Oregonian (November 2, 1915).

[11] “Oregon Sculpture Is Seen by Public,” Portland Oregonian (November 12, 1915).

[12] Ledger 2, p. 67, and ledger 5, p. 308, Roman Bronze Works Archives, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, TX.

[13] A biographical sketch appeared in K. W. Fitzgerald, “Sheep King: John Edwards Wills Wool Fortune to Oregon,” Portland Oregonian (April 7, 1946).

[14] “C.S. Jackson Gives Characteristic Thanks for Present of ‘Buckaroo,’” Eastern Oregonian (January 22, 1917).

[15] Hassrick, Wildlife and Western Heroes, 192–93.

[16] See Janis Conner, “After the Model: Bessie Potter Vonnoh’s Early Bronzes and Founders,” in Julie Aronson (ed.), Bessie Potter Vonnoh: Sculptor of Women (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2008), 244.

[17] Figures from Proctor’s Account Book, 1930s, Proctor Archives.