On the Warpath; On the War Trail; The Scout

Banner Image: Alexander Phimister Proctor

On the War Path, 1928

Bronze, 20 3/4 in. (height). The Rees-Jones Collection, Dallas, Texas

On the first of May 1893, the gates of America’s grandest nineteenth-century extravaganza, the World’s Columbian Exposition, swung open to an eager public. As visitors—and there were millions of them that summer—wandered among the elaborate grounds and waterways and marveled at the exhibits and architectural wonders, they would have passed about a dozen monumental plaster sculptures of western wild animals, such as moose, elk, and mountain lions, that decorated the abutments of bridges provided to carry crowds over the fair’s many lagoons. They would also have encountered two heroic-sized plasters of epic western equestrian figures, one called Cowboy and the other titled Indian. [Plate 11.1] These monuments were all the work of a thirty-three-year-old New York sculptor named A. Phimister Proctor who had a reputation as a westerner, having been raised in Colorado, and as a fine artist, having studied at the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League.

Plate 11.1 — Unknown Photographer

Indian, 1893 (monumental plaster by Alexander Phimister Proctor)

Photograph, b&w. Alexander Phimister Proctor Collection, MS 242. Harold McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. MS242-OS3.2.3

Proctor’s Indian was deemed by the critics to be one of the more successful of his works at the fair, though they almost all garnered quite favorable mention.[1] He had used as a model none other than the son of the famous Sioux chief Red Cloud, Jack, who was part of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West troupe, which performed in an arena adjacent to the world’s fair grounds. He also adapted from one of Buffalo Bill’s posters the pose of a mounted and fully armed Indian warrior scanning the horizon with one hand shading his eyes against the prairie sun. [Plate 11.2] Proctor chose to portray the man and his horse in a dramatic fashion. The rider turns to the left in a gesture of immediate urgency, as if alerted to some danger in the distance. His horse, striding forward with a lifted, extended tail, is further animated as he twists his head and neck to the left acknowledging a similar threat.

Plate 11.2 — A. Hoen & Co., Lithographers, Baltimore, Maryland

An American, 1893

Lithographer, four-color poster, 38 1/2 x 27 1/2 in. Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Gift of The Coe Foundation. 1.69.51

An inveterate hunter, Proctor had many close encounters with wild animals of the Rocky Mountains as a young man. He had also rubbed shoulders with many cowboys in his day, as well as Indians. When in his late teens, in September 1879, he was hunting near Grand Lake on Colorado’s western slope, the Ute Wars broke out. Although not directly involved, Proctor was close to the action and later wrote a full, detailed chapter about the events in his autobiography.[2] Proctor’s sentiments seemed to favor the intractable agent for the White River Utes, who was involved, Nathan C. Meeker, yet he also evidenced a certain compassion for the lead figure in the Ute insurrection, Chief Colorow. It was a portrait of Colorow that illustrated Proctor’s chapter (6, “Colorado Indians”), not one of Meeker or those from the military who attempted to rescue him. Proctor was, in fact, so enamored of the Ute chief that, in the 1940s, he made a dry point etching of Colorow. [Plate 11.3]

During the Ute Wars, Colorow’s tribe was first bullied into abandoning its traditional hunting practices (continuing them would have competed with the likes of Proctor and his cronies), and then, after the tribe resisted, it was attacked twice by the formidable forces of the U.S. Cavalry. The attitude that Proctor selected for his monumental Indian at the World’s Fair was one of militant opposition, pride, and vigilance, reminiscent of Colorow’s actions. It was a stance that would inform Proctor’s later work, including the spirit of On the War Path.

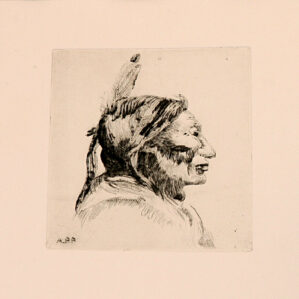

Plate 11.3 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

Chief Colorow, ca. 1940

Etching on paper, 9 x 6 1/2 in. Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Gift of A. Phimister Proctor Museum with special thanks to Sandy and Sally Church. 11.06.410

When the world’s fair concluded in 1894, the city of Denver asked to have two of its hometown artist’s works brought home to Colorado’s capital. Indian, along with Cowboy, were placed in Denver’s new City Park. There, despite their fragile medium, they remained into the mid-teens. They were still fresh in the public’s mind when Proctor proposed a couple of monumental western bronzes for the city’s emerging new Civic Center in 1917. Denver’s visionary mayor Robert Walter Speer pressed to have the earlier works replaced with new ones using the same themes but cast in enduring bronze. By the following summer, Proctor had begun work on his second Indian monument, what would be titled on the plinth at the time of its dedication in 1923 as On the War Trail.

Proctor first completed the horse in March 1919 and then the full maquette by late that fall. Its evolution showed how much devotion Proctor felt for that first Indian sculpture he had produced back in 1893 for Chicago. In both of the two early sketches for the new piece, [Plate 11.4] the warrior peers out while shading his eyes, as in his world’s fair Indian plaster, in a posture of reconnaissance.

Plate 11.4 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

On the War Trail (early model), ca. 1919

Photograph, b&w. Alexander Phimister Proctor Collection, MS 242, Harold McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. P.242.838

But more than his initial work influenced this fresh interpretation. The Indian’s horse has been pulled to an abrupt stop with its forelegs extended stiffly forward, and the warrior tucks his legs and feet back toward the horse’s rump, all similar to the pose employed by Proctor’s contemporary Cyrus Dallin in his 1904 bronze Protest. [Plate 11.5] Dallin’s Protest had been displayed at the 1904 world’s fair in St. Louis, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, where it had won a gold medal. Proctor was no doubt quite familiar with it.

Plate 11.5 — Cyrus Edwin Dallin (1861 – 1944)

A Protest, 1904

Bronze. Illustration in Arts & Decorations Magazine (February 1914 ), 153. Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming

Proctor used three Indian models as he developed the Denver Civic Center monument and its various reductions. Jackson Sundown, the Nez Perce model for his Buffalo Hunt, began the process. However, Sundown grew homesick after a while and returned to Idaho before the final concept for the piece had matured.[3] Proctor then found a Blackfeet model named Spotted Eagle in Glacier Park, Montana.[4] But that association did not endure, and he had to look farther afield. For the final iteration of the piece, he retained an accommodating, handsome, and good humored man from the Blackfeet Reservation. His name was variously noted as Big Beaver and Red Belt.[5]

The final prototype for Proctor’s tribute to native resistance changed the Indian’s gesture from one of hesitant scouting to one of full-scale belligerence. As with the story of Chief Colorow, the protagonist here is prepared to stand his ground and fight. Unlike Dallin’s version, in which the chief raises his fist in futile desperation, Proctor’s interpretation reflects Colorow’s existential heroism when he defeated the first surge of U.S. military and stood resolutely, though ineffectually, against a much larger subsequent force sent to subdue him. Proctor met the old chief a few years later, and in the artist’s autobiography, he wrote admiringly of Colorow’s perspicacity and valor.[6] In the monumental version of the sculpture as situated in Denver, a belligerent warrior faces the city center. [Plate 11.6] The city was filled with Anglos who had profited from the government’s decision after the Ute Wars to remove the White River Utes to a remote corner of Utah. There the Indians would pose no threat. Their ancestral land could then serve as a rich resource for ranching and mining. The bronze warrior with his spear aspired to metaphorically pierce that bubble of greed and messianic Anglo assumptions about removal and acculturation.

Plate 11.6 — Unknown Photographer

On the War Trail (monumental bronze by Alexander Phimister Proctor), ca. 1919

Photograph, b&w. Alexander Phimister Proctor Collection, MS 242. Harold McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. P.242.880

Perhaps because of Proctor’s not-so-subtle message with this bronze, small versions of the work were never big sellers. The piece was cast in two sizes, a 20-inch-high version and one that measured 48 inches, derived from a plaster that had served as the maquette for the monument. There are about four known copies of the smaller piece and just one of the larger.

On the War Path has had several titles over the years. Its first known mention as a tabletop-sized bronze appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle in November 1919 as the Scout.[7] A month later the Denver Post referred to it as On the Warpath.[8] By 1922, the same year the monument was dedicated in Denver as On the War Trail, Proctor began showing smaller, tabletop versions of the work from coast to coast. That year, the National Academy of Design in New York and the Bohemian Club in San Francisco both presented castings in their galleries, the former as On the War Trail and the latter as On the War Path.[9] Proctor finally copyrighted the piece in May 1923 as On the War Path (the title chosen here as the primary one).

Plate 11.7 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

On the War Path (detail – foundry mark), ca. 1928

Bronze. Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Philip Cole Collection. GM 0137.81

Plate 11.8 — Alexander Phimister Proctor

On the War Path, ca. 1921

Bronze, 48 in. (height). Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. Bequest of Arthur Rubloff. 2004.1155

Proctor cast examples of the 20-inch version of On the War Path with Roman Bronze Works, probably around 1928 (Rees-Jones Collection); Gorham Co. Founders in 1928; and in Brussels with Ancienne Foundeur National Bronzes, L. Petermann, also around 1928 (Gilcrease Museum). The Petermann cast produced in Brussels is thought to be the first in the series. It is marked with a signature and Dutch inscription “A P Proctor.Remodelert.” [Plate 11.7]It is thought that Proctor took the large plaster of the monument maquette to Rome and Brussels with him and did the reduction in the latter city. Remodelert is Dutch for “remodeler.” There are no substantial differences between the three known small versions except for patinas and the fact that the Petermann example is sand cast and the other two lost wax. When he cast the one known example of the 48-inch version, he used Roman Bronze Works and the lost wax method. [Plate 11.6]

[1] Coffin, “The Columbian Exposition—I,” 81.

[2] See Ebner, Sculptor in Buckskin, 41–45.

[3] “World Artist, Executing Indian Scout Statue, Busy in His Los Altos Studio,” San Jose Mercury Herald (March 23, 1919).

[4] See “Carries His Indian Model with Him,” The Spectator (Portland, Ore.), December 1919.

[5] “‘Red Belt,’ Indian Model of Sculptor Discovers Pacific,” Daily Palo Alto Times (October 27, 1919).

[6] Ebner, Sculptor in Buckskin, 45.

[7] “Artist Takes Indian Model East with Him,” San Francisco Chronicle (November 30, 1919).

[8] Arthur Frenzel, “A. Phimister Proctor, One of the Early-Day Westerners, Will Put Up Monument Where Once He Played Ball,” Denver Post (December 26, 1919).

[9] See Peter Hastings Falk (ed.), The Annual Exhibition Record of the National Academy of Design, 1901–1950 (Madison, CT: Sound View Press, 1990), 426; and “Statues by Proctor Mark Club Exhibit,” San Francisco Chronicle (January 25, 1922).